In summer 2018, on occasion of the retrospective devoted to the Pakistani artist Rasheed Araeen, MAMCO was inaugurating the first phase of its reflections concerning the internationalization of its exhibition corpus and the emergence of a world art history.

The political relationship that Rasheed Araeen has with so-called “minimal” forms, and his commitment to postcolonial theory, gave his practice an exemplary value in the “de-colonization” process of art history in the second half of the 20th century. For, the Western hegemony of museums and historiographical institutions had imposed the myth of a “universal museum of modern art” whose truly ideological nature can now be gauged. It is thus both the resonances of an evolutionary and progressive vision of art history, and the cultural contexts under consideration, which have today been put into question by the inclusion of other narratives.

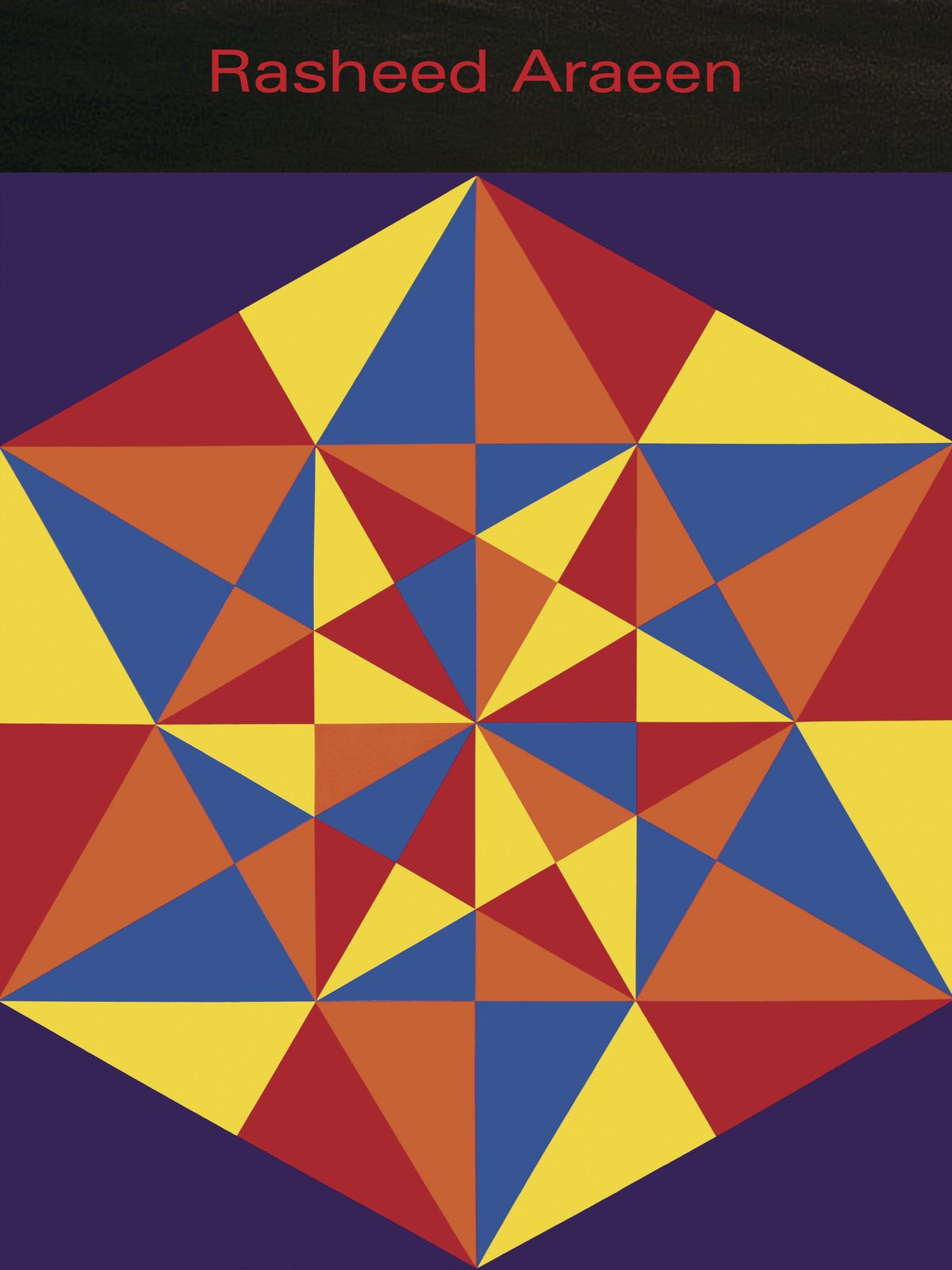

Rasheed Araeen was born in 1935 in Karachi (Pakistan), where, with no formal artistic education, he produced his first works during the 1950s, which already attested to his interest in the geometric compositions suited to an expression of his impressions. When he arrived in London in 1964, as a qualified engineer, Araeen was struck by Anthony Caro’s colored metal sculptures. By the end of the 1960s, he had developed his own language, based on the use of simple forms, and the notion of symmetry, as can be seen in his first Structures. Apart from their constructive and minimal aspect, these sculptures are also an invitation to a relationship with the spectators, who can sometimes alter their arrangements. The retrospective, spanning a 60 years’ career, leads the visitors through five chapters, from the works of the 1950s, through the sculptures of the 1960s and 1970s; then, following his increasingly affirmed political commitment in the 1980s, to the series of cruciform panels from the 1980s-1990s; and his most recent pieces, brought together under the title Homecoming.

As Nick Aikens explains, Araeen’s practice has constantly rethought the formal, ideological, and political affirmations of Eurocentric modernism. This questioning lies at the heart of his practice, both in artistic and intellectual terms. It fed both into his involvement with the Black Panthers movement in the 1972, and the setting-up of the review Third Text in 1987. It underlay his performances in the 1970s, and his para-minimal Structures. What is more, it led to his identity self-portraits from the early 1980s and his photographic compositions from the same period. And, as we can be reminded by the paintings from the recent Opus series, inspired by Islamic decorative art, Araeen responds to the universalist pretentions of Western modernism by an affirmation of the multiple origins of abstract language.

Yet, the globalizing imperative to bring in “differences” is not enough to resolve the issues coming from a dominant ideology. For a museum like MAMCO, what is at stake is rather to gauge to what extent taking into account these differences modifies our understanding of the forms and practices we collect. What should be considered is our conception of recent historiography, and the division of its periods, as much as the aesthetic contours applied to the movements in question. For example, how we do see the museum collection containing the work of Siah Armajani (*1939), an Iranian artist who emigrated to the USA, or of Julije Knifer (1924–2004), a Croatian artist who was based in Paris, through the prism of Rasheed Araeen’s show? Can the equation that this artist has established between symmetry and democracy help to shed light on the symbolism at the heart of Armajani’s work? Doesn’t the irony in his re-combinable Structures bring to mind the view that the members of the Gorgona group, with whom Knifer participated between 1959 and 1966, had of creation? In other words, is it possible for a museum to construct different conceptual tools, aesthetic categories, and other narratives of the passing of time as we see it, while exhibiting these artists, and thus exposing ourselves to such forms?

- Exhibition curated by Nick Aikens and Paul Bernard

- With the support of the Stanley Thomas Johnson Stiftung